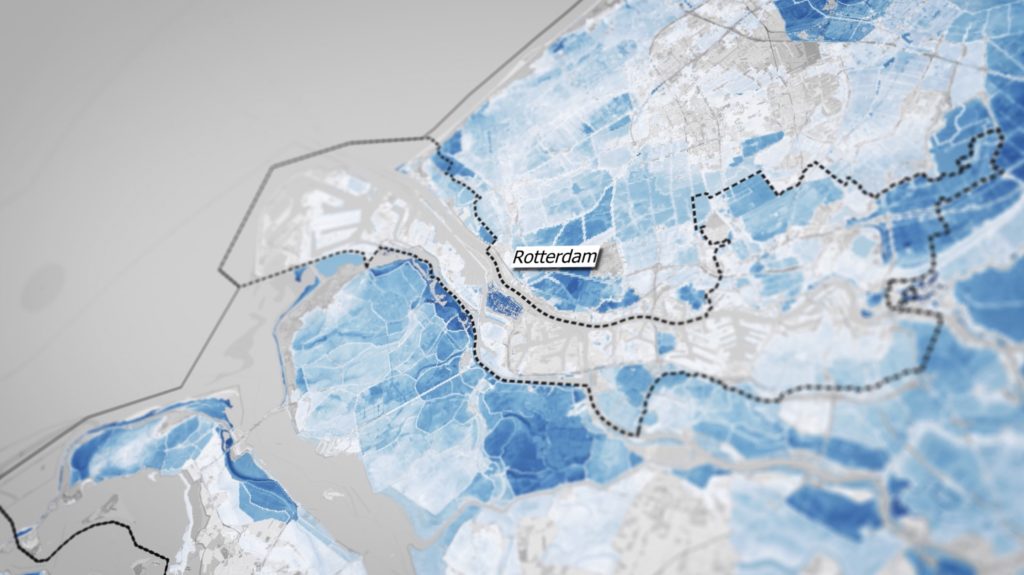

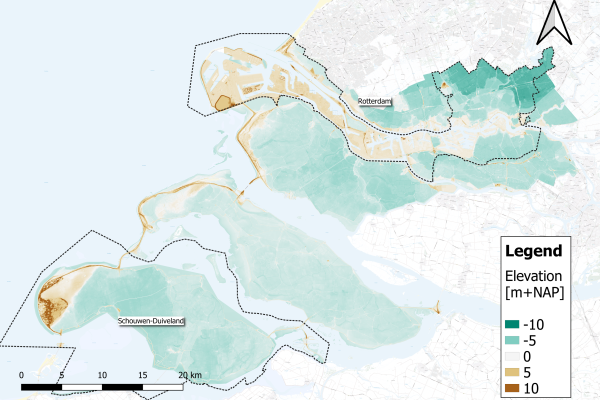

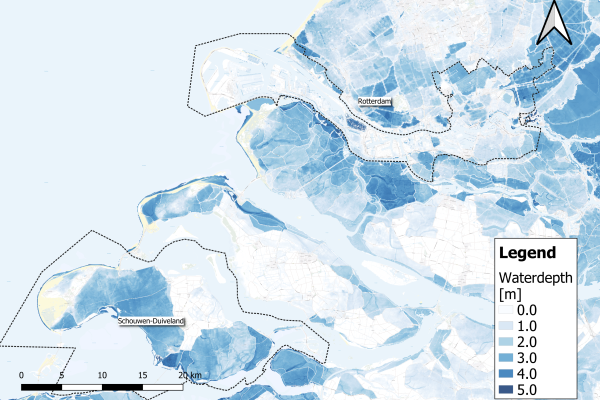

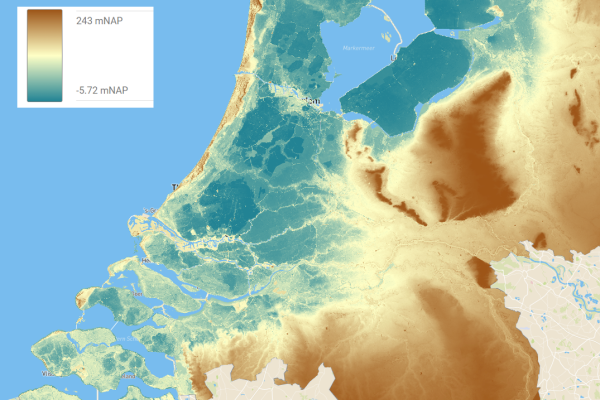

During the night of 31st of January 1953, a sea storm surge broke through the Netherlands’ protective barriers and flooded roughly 10% of the country; the UK and Belgium were also impacted. In the Netherlands, 1836 people died, and the total cost of damage was equivalent to around €5.4 billion today. Much more recently, in summer 2021, floods caused by heavy rains in the province of Limburg led to hundreds fleeing their homes. With climate change expected to trigger more extreme weather events and raise sea levels by 15-40 cm by 2050, there is a growing need for this low-lying land to plan ahead. Dutch partners in the EU-funded IMPETUS project are developing digital decision-support tools for municipal spatial planners, so they can create more sustainable cities and communities, with a focus on the southern city of Rotterdam and surrounding areas in Rijnmond and the province of Zeeland. Their flooding decision support system will help the region adapt to increasing flooding risks in the face of climate change.

Risks and responses

There are a number of ways in which flood risk is increased due to the climate crisis. Alongside rising sea levels due to melting ice caps, a warmer atmosphere can hold more water which leads to more intense periods of rainfall. Already this decade, one third of Pakistan was submerged during a monsoon season, and German river banks burst killing 220 people in the same incident that caused flooding in Limburg.

“People didn’t know where to go – they didn’t know where to flee, and which areas were safe,” says Fons Nelen, referring to the Limburg floods. He’s the director of Nelen & Schuurmans, a water management consultancy company based in Utrecht. “You can save a lot of lives, and you can prevent a lot of damage, if you have the right information at the right time.”

“Flood risk is always happening very fast,” says Nelen. “So you see a storm coming and you have to know what to do – it’s always a matter of hours.”

Developing solutions

As the threat of another countrywide flood rises alongside global temperatures, Dutch engineers like Nelen are working hard to come up with solutions. Within Nelen & Schuurmans, they’re building models that incorporate information about all the ways water moves within the country, from the sea, rivers and sewers, to real-time meteorological information.

Such technology has already been deployed in a warning system in the Parramatta river in Sydney, Australia. “There is a warning level… if it starts raining, people get information when a certain threshold is reached,” he says. “We think that, where every end user nowadays is used to getting weather information, the next step will be that everybody gets information on flood risks.” The World Meteorological Organization agrees, as they advocate for flood risk information for everyone by 2030.

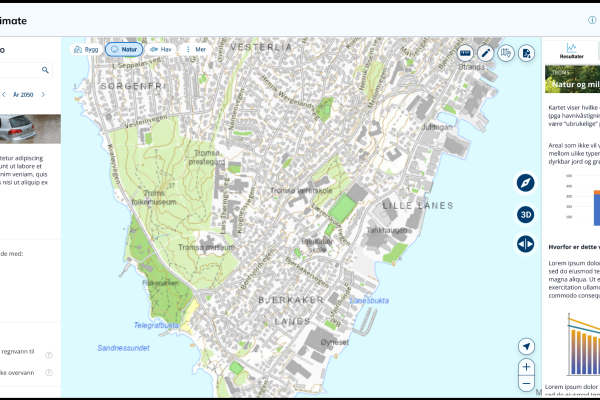

Martine Rottink, a consultant at Nelen & Schuurmans, says that the tool they’re developing –software that will host the models they’re creating – will be used by municipalities, rather than the general public. After developing a demonstration, they recently showed the tool to potential users and are currently implementing the feedback before finalising development. One piece of feedback was that it was nice to have data about flooding, but users need more guidance on practical steps they could take – according to Rottink.

This work is part of the EU-funded IMPETUS research project, which is finding ways to turn climate commitments into tangible actions to protect communities. “We began with the project in 2021, and we are planning to finish in 2025,” she says. In the project, the team is focusing on how to make the city of Rotterdam, its port and surrounding area more resilient to sea level rise.

Practically, Rottink says that the tool can be used to plan ahead when it comes to flood risk. “In the Netherlands, we have put our faith in dikes and barriers to protect us against sea and river flooding and have focused almost solely on flooding prevention,” she says. “But pressure on our system will increase with climate change: to adapt and maintain a safe living environment, we need other safety measures, like robust contingency and spatial planning.”

Planning to prevent problems

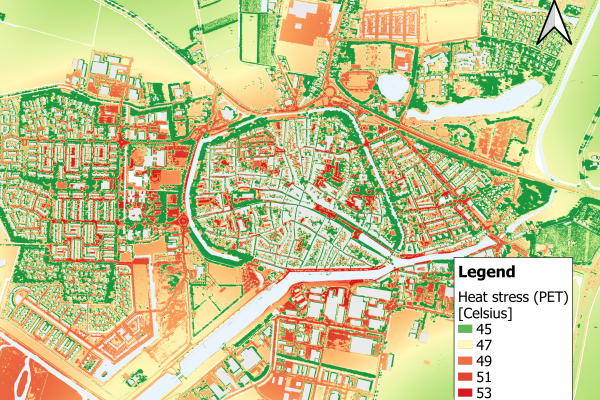

Another factor Rotterdam will need to deal with is more intense rainfall. “Because of climate change, we see problems with rainwater in our city,” says Johan Verlinde, Program Director for climate adaptation with the municipality of Rotterdam. “We see that the average annual rainfall is about the same, but it falls in a shorter amount of time, especially in summertime.”

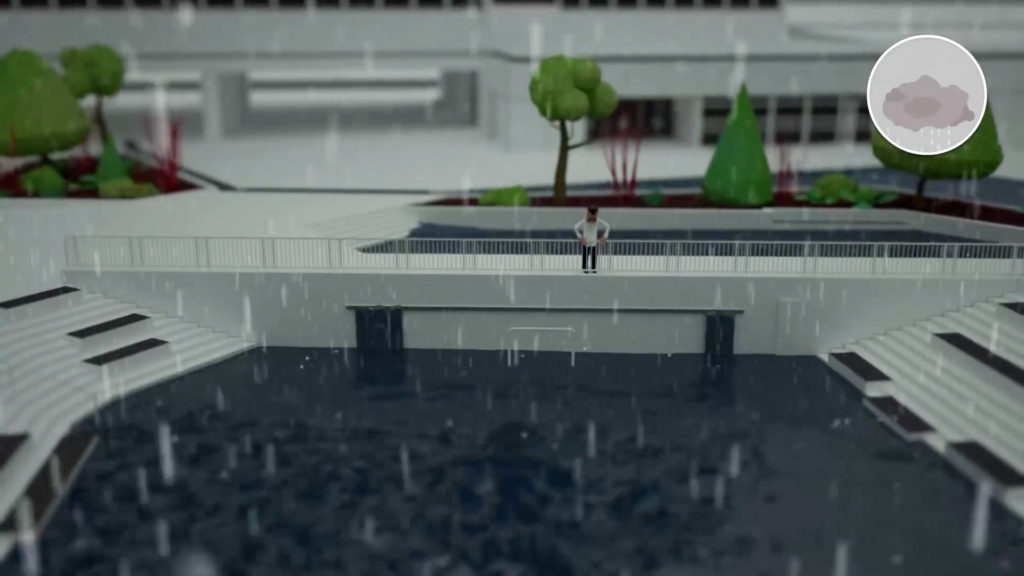

Intense rainfall can overwhelm the city’s sewer system. To stop this leading to flooding, the municipality of Rotterdam has built a number of small reservoirs within the city. These hold water for around 24 hours before releasing it into a chamber where it can soak into the ground and become groundwater, without entering the sewer system.

Such city infrastructure has to be multifunctional. Each reservoir’s design is unique, as the planners take local citizens’ preferences into account. For example, one reservoir can be used for skating and has a space to host performances. “We want to make the city climate proof in a way that’s also more attractive to our citizens,” Verlinde says. “It’s not only about technical solutions below the surface, it’s also about adding small parks or making the buildings more green.”

According to Fons Nelen, urban planners and landscape engineers have been taking climate risks into account only for around the past ten years. Although the chance of flooding is still low – even in the low-lying Netherlands – if it does happen, the impact can be very high, as the floods of 70 years ago and more recently showed. “If we are able, within the IMPETUS collaboration, to demonstrate the use and capabilities of digital decision-support technology, our ambition is to apply it worldwide